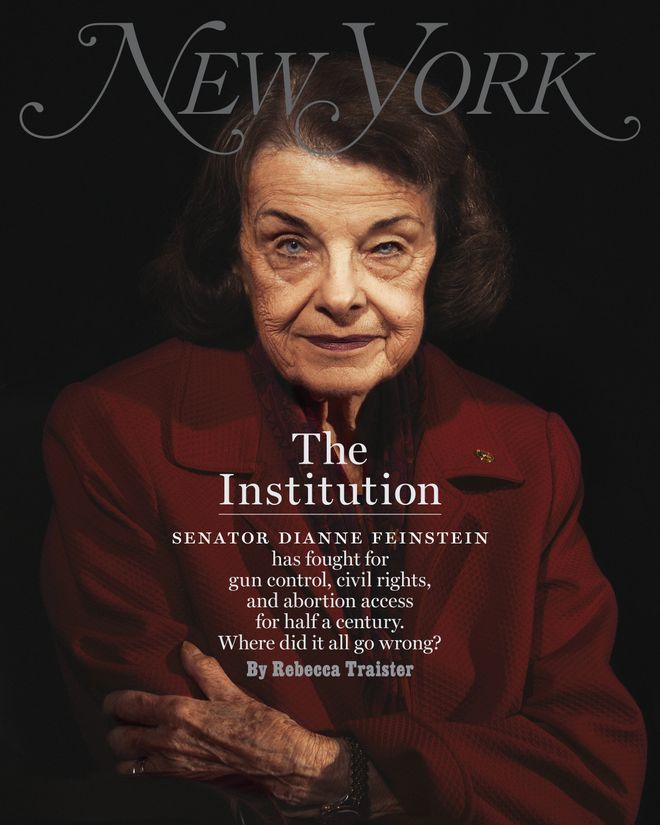

Editor’s note: This story was originally published on June 6, 2022. On September 29, 2023, Senator Dianne Feinstein died at age 90. In this New York cover story, Rebecca Traister considered Feinstein’s career and its place in the ebb and flow of the women’s movement since the 1970s.

On election night in San Francisco in 1969, a 36-year-old woman who had run a campaign for the Board of Supervisors that featured the unconventional use of just her first name, Dianne, was waiting anxiously for results in a race she was not expected to win. The local media had barely covered her. She had earned the endorsement of only one elected official, the state assemblyman Willie Brown. She had initially run the race out of her own house and had taken a risky, forward-looking tactical approach: cultivating support from the city’s growing population of gay voters and environmental conservationists.

As the returns began to trickle in, “it soon became clear that a big local story was unfolding,” Jerry Roberts later wrote in his 1994 book, Dianne Feinstein: Never Let Them See You Cry. “Dianne was not only winning, she was topping the ticket, an unheard-of showing for a nonincumbent, let alone a woman.”

Feinstein was so reluctant to believe the early returns that she had to be persuaded to go to headquarters on Election Night. When she entered the room, she “was thronged by an emotional crowd,” Roberts wrote. One of her supporters joked about “painting City Hall pink.”

The next day, San Francisco’s daily papers blared news of Feinstein’s stunning upset on their front pages. The press homed in on Feinstein’s “dark-haired, blue-eyed beauty” and made sure to note that the woman who would, as the top vote-getter, soon assume control of the Board of Supervisors was dressed in “a fashionable blue Norell original with a bolero top and a wide white belt.”

It’s hard to read about that night and not think of an evening 49 years later, when 28-year-old Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez shocked New York City by winning her scrappy primary campaign for Congress, sending a rush of reporters to belatedly cover a phenomenon known as “AOC,” fetishizing her clothes, her hair, her face. Both women’s entrances into politics were watershed moments. As Feinstein told reporters at the time, her win signaled “a new era, a different kind of politics working strongly for change,” saying of her then-12-year-old daughter’s interest in one day being mayor, “Each generation does better than the one before.”

Cover Story

Feinstein’s career in American politics, a series of historic firsts that began with her leading the Board of Supervisors, was born in the upheaval of the mid-20th century’s struggles for greater civil rights. There was a conviction that Feinstein’s rising generation of Democrats, more diverse than any that had preceded it, would be the stewards of those hard-won victories. “I was sort of intoxicated with my win,” Feinstein told Roberts of that big night in 1969. “I had done something that hadn’t been done before. I didn’t understand what loss was like in the arena.”

Since then, Feinstein has lost as much as she has won. She has lost two husbands to cancer, two colleagues to assassination, and tens of thousands of her city’s residents to the AIDS epidemic. She served on the Board of Supervisors for eight tumultuous years, and she ran and lost two mayoral races before serving as mayor of San Francisco for nine years. She was considered and passed over as a vice-presidential candidate in 1984, lost a California gubernatorial election in 1990, then won six elections to the United States Senate, where she serves as the fifth-most-senior senator.

Feinstein is now both the definition of the American political Establishment and the personification of the inroads women have made over the past 50 years. Her career, launched in a moment of optimism about what women leaders could do for this country, offers a study in what the Democratic Party’s has not been able to do. As Feinstein consolidated her power at the top of the Senate, the party’s losses steadily mounted. It has lost control of the Supreme Court; it is likely about to lose control of Congress. Children are being gunned down by the assault weapons Feinstein has fought to ban, while the Senate — a legislative body she reveres — can only stand by idly, ultimately complicit. States around the nation are banning books about racism as Black people are being shot and killed in supermarkets. Having gutted the Voting Rights Act, conservatives are leveraging every form of voter suppression they can, while the Senate cannot pass a bill to protect the franchise. The expected overturning of Roe v. Wade this summer will mark a profound step backward, a signal that other rights won during Feinstein’s adulthood, including marriage equality and full access to contraception, are just as vulnerable.

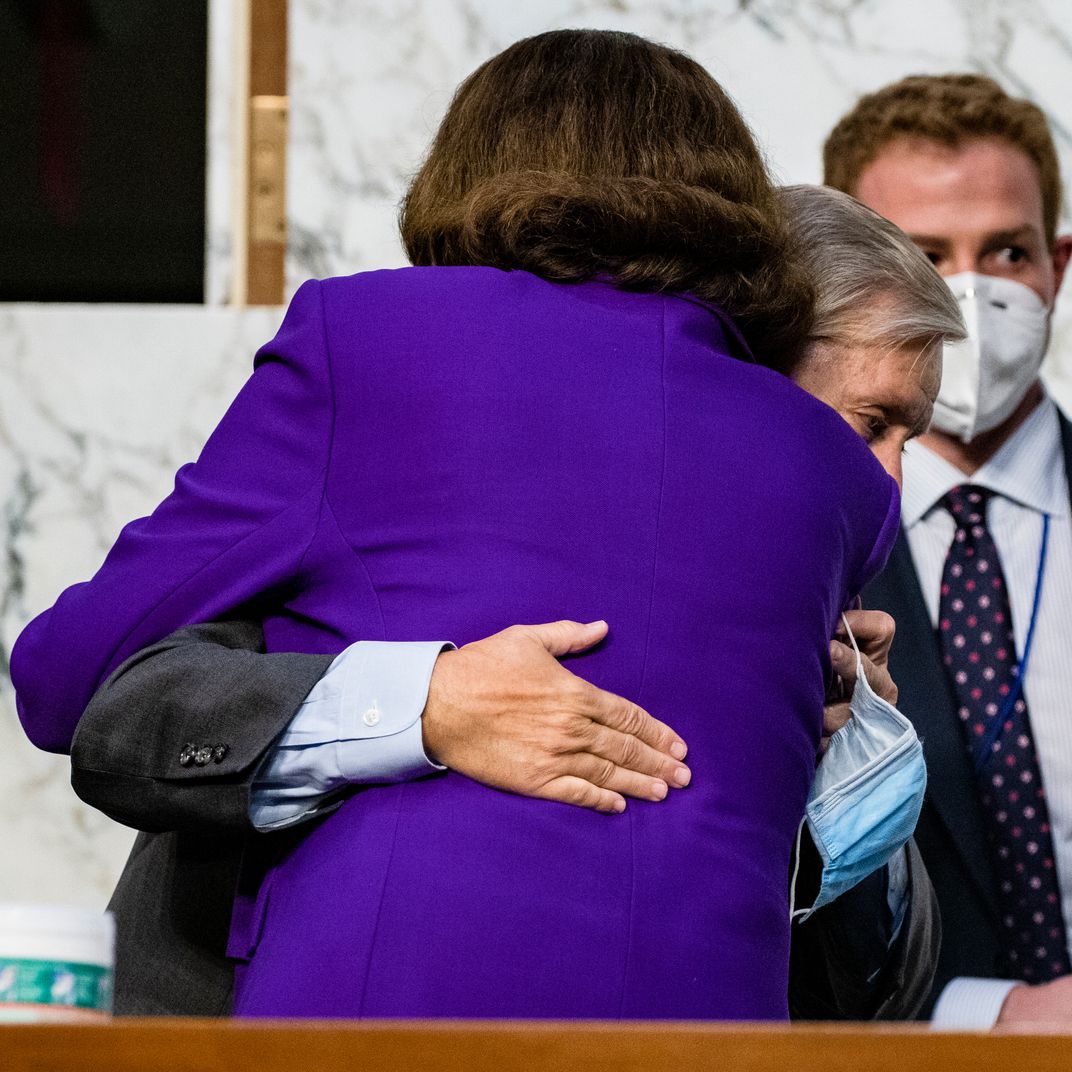

As the storied career of one of the nation’s longest-serving Democrats approaches its end, it’s easy to wonder how the generation whose entry into politics was enabled by progressive reforms has allowed those victories to be taken away. And how a woman who began her career with the support of conservationist communities in San Francisco, and who staked her political identity on advancing women’s rights, is now best known to young people as the senator who scolded environmental-activist kids in her office in 2019 and embraced Lindsey Graham after the 2020 confirmation hearings of Amy Coney Barrett, a Supreme Court justice who appears to be the fifth and final vote to end the constitutional right to an abortion. As Feinstein told Graham, “This is one of the best set of hearings that I’ve participated in.”

For many from a younger and more pugilistic left bucking with angry exasperation at the unwillingness of Feinstein’s generation to make room for new tactics and leadership before everything is lost, the senator is more than simply representative of a failed political generation — she is herself the problem. After she expressed her unwillingness to consider filibuster reform last year, noting that “if democracy were in jeopardy, I would want to protect it, but I don’t see it being in jeopardy right now,” The Nation ran a piece headlined “Dianne Feinstein Is an Embarrassment.”

Feinstein, who turns 89 in June, is older than any other sitting member of Congress. Her declining cognitive health has been the subject of recent reporting in both her hometown San Francisco Chronicle and the New York Times. It seems clear that Feinstein is mentally compromised, even if she’s not all gone. “It’s definitely happening,” said one person who works in California politics. “And it’s definitely not happening all the time.”

Reached by phone two days after 19 children were murdered in an elementary school in Uvalde, Texas, in late May, Feinstein spoke in halting tones, sometimes trailing off mid-sentence or offering a non sequitur before suddenly alighting upon the right string of words. She would forget a recently posed question, or the date of a certain piece of legislation, but recall with perfect lucidity events from San Francisco in the 1960s. Nothing she said suggested a deterioration beyond what would be normal for a person her age, but neither did it demonstrate any urgent engagement with the various crises facing the nation.

“Oh, we’ll get it done, trust me,” she assured me in reference to meaningful gun reform. Every question I asked — about the radicalization of the GOP, the end of Roe, the failures of Congress — was met with a similar sunny imperviousness, evincing an undiminished belief in institutional power that may in fact explain a lot about where Feinstein and other Democratic leaders have gone wrong. “Some things take longer than others, and you can only do what you can do at a given time,” she said. “That doesn’t mean you can’t do it at another time. And so one of the things that you develop is a certain kind of memory for progress: when you can do something in terms of legislation and have a chance of getting it through, and when the odds are against it, meaning the votes and that kind of thing. So I’m very optimistic about the future of our country.”

It is not a comment on her age to note the sheer amount of history that has determined Dianne Feinstein’s life.

Her father, Leon Goldman, was born in 1904 to Jewish immigrants. Feinstein’s grandfather had fled pogroms in Russian-occupied Poland and had become a shopkeeper in San Francisco, where the family’s lives were upended by the fire that raged after the 1906 earthquake. The family relocated to Southern California, and Feinstein’s grandfather invested in oil wells. Leon would go on to medical school, becoming the first Jewish chair of surgery at the University of California, San Francisco, hospital and a member of San Francisco’s rarefied social circles.

Feinstein’s mother, Betty Rosenburg, fled the Bolshevik Revolution with her czarist Russian Orthodox father, traveling across Siberia by hay cart. She grew up to be a model, and after marrying Goldman and bearing three daughters, she became alcoholic, abusive, and suicidal. She raged and threatened to kill Dianne and her sisters, calling them “kikes” and “little Jews,” and once tried to drown her youngest daughter in a bathtub.

This instability remained a secret in the upscale circles in which Feinstein’s parents moved. Her father was a workhorse, adored by his patients and his eldest daughter; many think she modeled her workaholic habits and insatiable ambitions on his. “Dianne is really Leon Goldman in the garb of a beautiful woman,” one family friend told Roberts.

Raised Jewish, Dianne was nonetheless enrolled as a teen at the exclusive Convent of the Sacred Heart High School in tony Pacific Heights, where she became quite taken with the aesthetics of Catholic ritual and hierarchy. The school was full of processions and teas and ceremonies. Students were required to wear starched uniforms and white gloves. In his book Season of the Witch, San Francisco writer David Talbot reported that young Dianne would occasionally try on a nun’s habit.

Dianne attended Stanford, where she won the highest political position available to female students at the time: the vice-presidency. She got a fellowship the year after her graduation, in 1955, during which she worked on a report about criminal justice in San Francisco. She eloped with the man who would become her first husband and got pregnant, giving birth to her daughter, Katherine, in 1957. Within two years, she would be divorced and a single mother at 26, albeit a very privileged one. In her mid-20s, she briefly entertained the idea of becoming a stage actress, took up sailing, and volunteered for John F. Kennedy’s 1960 campaign. When, in 1961, a San Francisco real-estate developer refused to show a home to a rising-star Black lawyer, Willie Brown, Dianne brought her daughter to a demonstration for Brown and bumped her stroller into Terry Francois, who was the head of the local NAACP. Both Francois and Brown would become close associates.

That same year, California governor Pat Brown, a patient of Dianne’s father’s, offered her a paid job on the California women’s-parole-and-sentencing board. For six years, she had the power to determine sentence length for women who had been convicted of everything from public drunkenness to violent crimes. She took a reformist approach to criminal justice, calling for rehabilitation rather than long sentences in narcotics cases. Francois, who had become the first African American to serve on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, assigned her to an advisory committee on local jails; she reported on the terrible state of the facilities, the inedible food, the overcrowding, the rampant vermin.

As part of her work with the board, she found herself determining sentences for abortion providers. Although she would later strongly support abortion access and often told a story about how, back at Stanford, classmates had passed a plate to pay for a student to travel to Tijuana to end a pregnancy, in the early ’60s the procedure was still illegal in California, and, as she would explain to Roberts, the cases in front of her were “all illegal back-alley abortionists. Many times, the women that they performed an abortion on suffered greatly. I really came to believe that the law is the law.”

Feinstein’s memories of this period remain sharp. “Under the indeterminate-sentence law, most sentences carried a low of maybe six months and a high of ten years,” she told me by phone. “There was one case, her name was Anita Venza. And over and over, she committed abortions on women. I said when we were sentencing her, ‘Anita, why do you continue doing this?’ And she said, ‘I feel so sorry for women in this situation.’ ”

I asked Feinstein whether she had continued to sentence Venza despite this explanation. “Yes.”

But did Feinstein feel for her? “Oh, yes,” she replied. “But she was a dedicated … She was going to continue to do it. There’s no question. She had been in state prison and been paroled and was brought back.”

When I pushed further, asking Feinstein what it felt like now to be on the verge of a future in which providers like Venza could once again be sentenced to prison, and in which the law will once again be the law, she declined to fully acknowledge the chilling implications of the rollback on the near horizon, retreating instead behind impenetrable platitudes. “Well, one thing I have seen in my lifetime is that this country goes through different phases,” she said. “The institutions handling some of these issues have changed for the better. They’ve become more progressive, and I think that’s important.”

Feinstein’s 1969 race for the Board of Supervisors might have found echoes in Ocasio-Cortez’s groundbreaking 2018 campaign, but the differences between the two women’s early paths are stark. Ocasio-Cortez ran a low-budget grassroots campaign out of her small Bronx apartment and was outspent by Joe Crowley, her heavyweight Democratic-primary opponent, 18 to one. Feinstein’s friends-and-family campaign, in contrast, was funded by San Francisco’s elite and entailed auctions of Ansel Adams prints and a free surgery by her father. It was what many believed at the time to be the most expensive campaign in San Francisco’s history.

Like a cartoon of efficient, rule-bound, Tracy Flick–style white femininity, Feinstein promptly threw herself into her role as the head of the board, San Francisco’s city council, transforming it from a part-time civic gig into a full-time study in technocratic control. She got there early and stayed late while her fellow supervisors, who needed actual jobs to support themselves, showed up when they could. “She crafted reams of legislation,” Roberts writes, “convened citizen advisory committees, performed ceremonial functions, demanded reports from bureaucrats.”

Feinstein’s profile grew. She ran for mayor in 1971 and lost, and lost again in 1975, but she retained leadership of the board through the ’70s, when things got weird in San Francisco. She believed in law enforcement and institutional control over the uncontrollable impulses of a city that was undulating with change.

In 1973, San Francisco was ravaged by the so-called Zebra serial killings. The next year, heiress Patty Hearst was kidnapped by the Symbionese Liberation Army, whose members had assassinated the superintendent of the Oakland schools. In 1975, the city’s police went on strike, and there was an assassination attempt on President Gerald Ford when he visited the city. Meanwhile, a group called the New World Liberation Front was connected to more than 70 bombings in Northern California, including at the San Francisco Opera House and the homes of some local executives.

Feinstein and several of her colleagues on the board were warned that they were targets. Packages full of dynamite were delivered to two board members, and in December 1976, when Feinstein was caring for her husband Bert Feinstein, then dying of cancer, a bomb was discovered outside 19-year-old Katherine’s window. It would have killed her except that the temperature had dropped that night, leading the device to misfire. The next year, the windows at Feinstein’s vacation home on Monterey Bay were shot out.

In the fall of 1978, Feinstein traveled to the Himalayas with the man who would become her third husband, financier Dick Blum. While there, she contracted dysentery and was forced to slow down, even as discontent grew on the board; one of Feinstein’s colleagues, a former police officer named Dan White, had become frustrated by money troubles, the policies of liberal mayor George Moscone, and the attention-getting successes of Harvey Milk, a liberal activist from the Castro who, in winning a spot on the board, had become the first openly gay man elected to political office in California. In the days that Feinstein had been at home with her intestinal ailment, White had abruptly quit his seat, then changed his mind and asked to be reinstated.

Feinstein advised Moscone to let him have his job back. But Milk despised White, telling the mayor that he would only impede his liberal agenda. Moscone eventually agreed with Milk and denied White’s request to be reinstated. On the morning of November 27, 1978, Feinstein, back to work for the first day after her trip and her illness, had been asked by Moscone to look out for an agitated White and calm him. Casually speaking to reporters as the board waited for the appointment of White’s replacement, she said that she would not be running a third mayoral campaign. While in Nepal, she had decided to leave politics.

“It’s important to remember that she thought her career was over before it even began,” said Cleve Jones, the labor and gay-rights activist who in 1978 was Milk’s student intern. “It was a very polarized city and she, as a moderate, felt there was no place for her. So she was going to give up politics.”

At around 10:30 a.m., Dan White entered through a basement window of City Hall and went to meet the mayor. Afterward, Feinstein heard her former colleague rushing by her. She couldn’t have known he had already shot and killed Moscone. “Dan,” she called to him. “I have something to do first,” White told her as he asked Milk to come into his office.

Feinstein heard the door of White’s office slam and someone shout, “Oh, no!” Then she heard shots and saw White running out of his office. When she entered, she found Milk’s body on the floor, surrounded by blood and brain matter. She reached down to take her colleague’s pulse and put her finger straight into the bullet hole on Milk’s wrist.

Jones arrived to find City Hall in chaos. “Dianne came rushing past me,” he said, “and I could see her hands and sleeves were stained with blood, and then I saw Harvey’s feet sticking out of Dan White’s office. It was the first time I’d ever seen a dead body.” Jones added, “There were many times when she and I disagreed, but I’ve always felt I share a bond with her that kind of transcends all this other stuff, because of what we both witnessed and how that day completely and absolutely transformed our lives.”

Feinstein, her tan suit covered in Milk’s blood, composed though in obvious shock, told the crowd at City Hall that Moscone and Milk had been killed and that the suspect was former supervisor Dan White. As the head of the Board of Supervisors, she then became San Francisco’s first female mayor.

Feinstein has maintained that her devotion to centrism was born of the tumult that led to her rise. “It was as if the world had gone mad,” Feinstein writes in Nine and Counting, a 2000 book about the nine women then serving in the U.S. Senate, describing her decisions to pursue the job of interim mayor in the wake of the assassinations and to run for reelection less than two years later. “The city needed to be reassured that there would be some consistency as we put the broken pieces back together … From that nonpartisan experience, I drew my greatest political lesson — the heart of political change is at the center of the political spectrum.”

This does not mean that Feinstein is a centrist, ideologically speaking. She has a solidly Democratic voting record and has occasionally taken positions progressively ahead of her party, though in other instances she has practically acted as a Republican. If she has hopscotched around the middle, it’s because she believes stability and progress — “the heart of political change” — flow from strong, functioning institutions built on consensus. It made Feinstein an odd fit for San Francisco in the late ’70s. As Talbot wrote, “San Franciscans had a fondness for lovable rogues and other colorful characters. But in a city of Marx Brothers, Feinstein was Margaret Dumont, forever distressed and befuddled by the antics around her.” In the wake of the assassinations, however, she became “precisely the right leader for the time.”

In her nine years as mayor of San Francisco, she grew ever more convinced that the balm for social upheaval and partisan protest was a tightening of civic authority. She inaugurated weekly meetings of city department heads, where the police chief always presented first. Just as she had taken to the starched clothes and white gloves and ceremonial displays of order at her Catholic school, Feinstein took up the aesthetics of local governance. She kept a fire turnout coat in the trunk of her car and would appear at blazes dressed like a firefighter; she was photographed in a custom-cut police uniform holding an emergency call radio and would listen to the police scanner while being driven around the city in her limousine.

Her mayoralty would overlap with the worst of the AIDS crisis. On this issue, too, her approach was to seek a middle path by giving and taking in turns. While on the Board of Supervisors, she had cast the deciding vote in support of Willie Brown’s legislation legalizing all private sex acts between consenting adults and proposed an ordinance to ban hiring or job discrimination against gays and lesbians — the first of its kind in the nation. But Feinstein had also spearheaded prim anti-pornography campaigns, and in her early years as mayor, she declined to sign a bill recognizing same-sex partnerships — despite offering her backyard for a same-sex commitment ceremony. She also provoked the fury of gay residents by closing the city’s bathhouses.

“I’m a very far-left union organizer and queer radical,” said Jones. “And buddies and I would go to a bathhouse and sit in that big Jacuzzi and conspire to drive Dianne nuts.” But, he added, “I remember talking with someone about how she was really walking a tightrope, the compassion she showed for people with HIV at a time of incredible stigma and misinformation and hysteria.” Jones’s appraisal is echoed in Randy Shilts’s defining account of the era, And the Band Played On, in which he notes that “of all the big-league Democrats in the United States, Feinstein was undoubtedly the most consistently pro-gay voice.”

Yet decades later she stayed away from the front lines of the movement for marriage equality. In 2004, she would publicly lambaste then-Mayor Gavin Newsom for issuing marriage licenses to gay couples in San Francisco, which she was sure provoked a conservative backlash that helped George W. Bush win reelection. “The whole issue has been too much, too fast, too soon,” Feinstein said after the 2004 election, betraying her tactical distrust of explosive social change. (She has since said that she was wrong on this.)

“It’s not just being in the middle so you can get votes in Fresno as well as Berkeley,” said Jones. “It’s that she believes in the power of the system to protect and manage. She’s all about order.”

After losing a 1990 bid for California governor, Feinstein ran for a vacant Senate seat in 1992. She, fellow Californian Barbara Boxer, Illinois’s Carol Moseley Braun, and Washington’s Patty Murray all won their races that year, doubling the number of women in the Senate (there had never before been more than two serving at one time). It was dubbed “the Year of the Woman,” part of an election cycle fueled by outrage over the treatment of Anita Hill at Clarence Thomas’s confirmation hearings in 1991, in which the all-white, all-male character of the Senate Judiciary Committee had been put on miserable display.

Even during that 1992 race, Feinstein’s willingness to adopt established norms was evident. “Pundits would remark that if there was a model for a woman senator, it would look like Feinstein,” recalled Rose Kapolczynski, who ran Boxer’s 1992 campaign. “In other words, a woman who looked and acted like male senators looked and acted.”

Still, it is hard to convey to those who have grown up in a world in which Feinstein and Boxer and Murray and Braun were the system, in which Hillary Clinton was considered, twice, the inevitable next president, in which Kamala Harris (the successor to Boxer’s California Senate seat) is now the vice-president, exactly what the victories of Feinstein and other women in her freshman class represented.

“I danced in the streets,” remembered the writer Rebecca Solnit, a longtime San Franciscan. “On Castro Street specifically, with lots of gay men, during the great 1992 election that brought Boxer and Feinstein into office. Feinstein feels like a bridge to me, a fixed point in the landscape that helped us cross out of the old, worse world, in which women were not senators.” But, she added, “we have traveled a long way from that bridge now.”

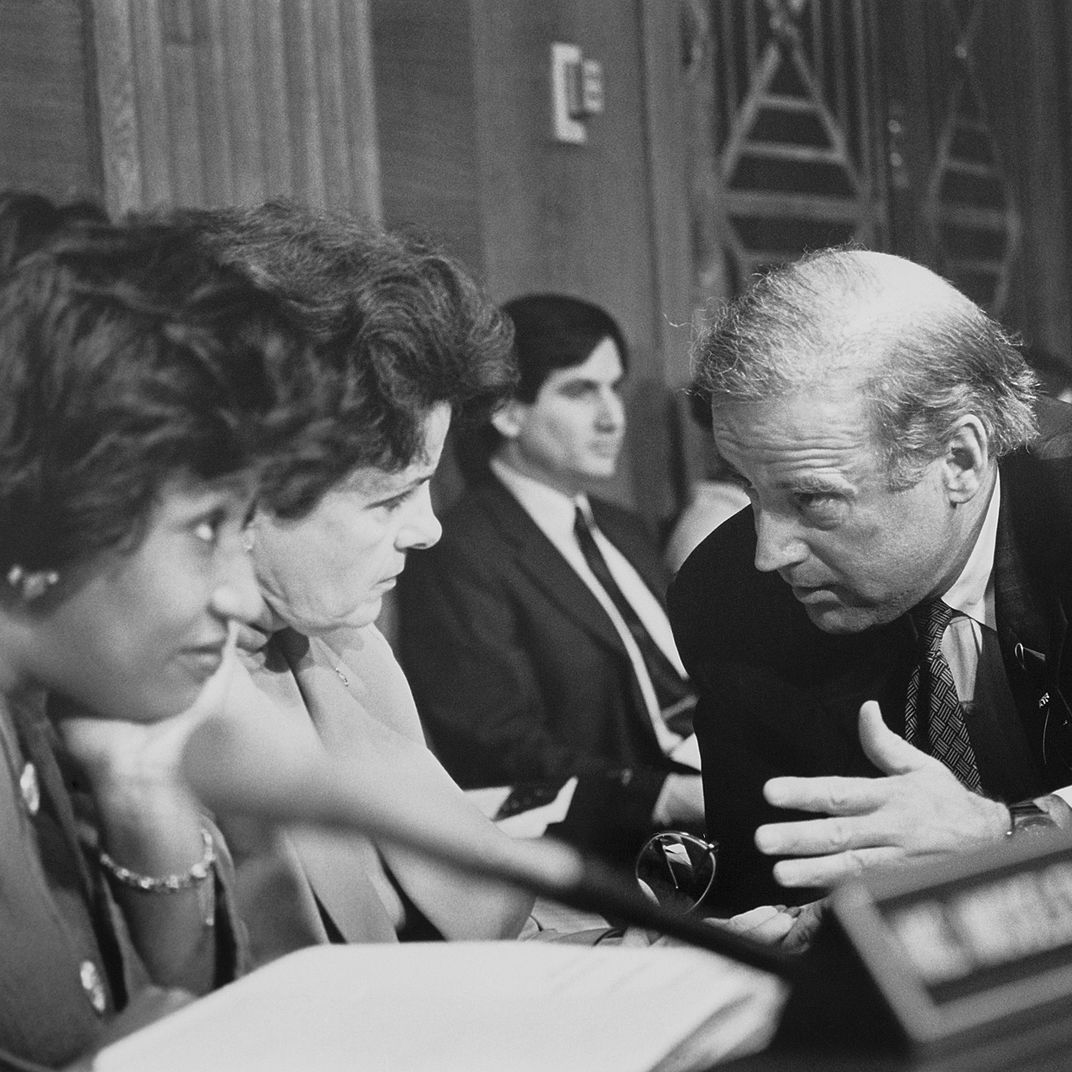

By its mere presence, the new cohort of women lawmakers was supposed to change how things worked in Congress or at least give the appearance of change. That function was made explicit to Feinstein and Braun, who were asked to do representational repair work on the Judiciary Committee.

“I walked away from that hearing convicted in the determination that I was gonna get women on that committee,” Joe Biden, who as committee chair notoriously failed to defend Hill from Republican attacks, says in the 2007 documentary 14 Women. “And I called Dianne.”

If women changed the Senate’s image, they did not always change its character. Political representation is a funny thing. The absence of women and minorities from governing institutions is ghoulish. But the seemingly obvious remedy — putting those people in power — can often involve new participants simply recapitulating the standards set by those who preceded them.

When Feinstein started in the Senate, she enforced its dress code, which reflected her own pearl-wearing respectability: No pantsuits for female staffers; they had to wear skirts or dresses. But even as Senate rules relaxed, Feinstein kept her standards intact. As recently as 2017 it was reported that women in her office were required to wear stockings and skirts of a certain length. Her very first speech on the Senate floor was in support of Bill Clinton’s landmark passage of the Family and Medical Leave Act, but when it came to the leave policy in her own office, she was behind the curve. In 2014, Feinstein’s office provided only six weeks of paid family leave, half of what many younger senators were offering both new mothers and fathers. (It’s 12 weeks now.)

Feinstein is, by multiple accounts, a terrifying boss to work for, famously stealing the old line “I don’t get ulcers; I give them.” During her race for governor in 1990, former employees, according to author Celia Morris, “called her imperious, hectoring and even abusive, claiming that she would dress down a hapless victim in front of others and would neither apologize nor admit it if she proved to be mistaken.” Within six months of her arrival in the Senate, 14 of her aides had departed (compared to three for Boxer), with 11 quitting and three fired.

Feinstein’s expectations of her staff have consistently remained sky-high. She has all of her aides — around 70 people — compile a two-to-four-page report of everything they did during the week, every week. Over the weekend, Feinstein reads them and then quizzes individuals on their reports in all-staff Monday meetings. Some saw these gatherings as democratizing. Others found them to be a tortured study in hierarchical protocols. Multiple former staffers spoke of the strict seating arrangements, with senior staffers around a middle table in a giant conference room, their aides in seats in a ring behind their bosses, and the most junior people standing at the periphery. “Everyone there had to be prepared, no issue too big or too small,” said one aide from the 1990s. “So it could be, ‘What is happening with the foreign-aid package?’ Or it could be, ‘I’m looking at a report of how many incoming letters we had and how many outgoing, and why is there such a backlog in responses?’ ”

“If you weren’t good at responding to that kind of Socratic interrogation technique, she didn’t make your job easy,” said the aide. “On the other hand, do I admire a senator who was as focused on how fast constituents got responses as she was on a foreign-aid package? I sure did.”

When a staffer left, if Feinstein liked them and they had served for a long time, she would give them prints of the still lifes she draws. If they were less special to her or had served briefly, she would give them a watch with her signature across its face. It could be difficult to leave her employment, several former staffers told me; she understood it as a slight. One former aide who took another job on the Hill remembered Feinstein saying, “It’s really unfortunate you are leaving; you had great potential.” When new people arrived in Feinstein’s employ, colleagues would surreptitiously hand them Jerry Roberts’s biography, with its details about her troubled, privileged childhood and her political coming of age in the crucible of San Francisco, with a whispered “Read this; it will all make sense.”

When stories have run about her bad behavior, Feinstein has shrugged them off. “When a man is strong, it is expected. When a woman is, it is not,” she told the Los Angeles Times in 1993. And she told her biographer, “When people act independently of the head figure, it causes conflicts. You can’t let staff run you. The person in charge has to be the guiding post.”

From the moment Feinstein got to the Senate, she embraced its rituals and practices, the clubby procedural stuff that at one time brought senators from competing parties together with a sense of their own power and responsibility — and sometimes even enabled them to get things done. “She is a model senator,” said Jeffrey Millman, who managed her 2018 campaign. “She loves this work, and she is really good at it.” But as with so much of her career, Feinstein’s record in the Senate is a mash of righteous fights and dispiriting capitulation, her ideological positioning scattered and her aims pragmatic, geared toward the goal of firm governance above all else.

As a young person reporting on California prisons, Feinstein fervently opposed capital punishment, but in 2004, she created an extremely awkward scene by going off script and making a call for the death penalty at the funeral of murdered police officer Isaac Espinoza. (More recently, challenged from the left, Feinstein has returned to her anti-death-penalty stance.)

She told me in our conversation that the institutions meting out criminal justice have become more progressive in the 60 years since she was on the sentencing board. But that’s not actually true, mostly because the kind of bipartisan cooperation Feinstein values so highly has centered on the expansion of a carceral state, via legislation like the 1994 crime bill authored by Joe Biden and supported strenuously by Feinstein.

When it comes to foreign policy, Feinstein has been a hawkish defender of drone strikes and expanded surveillance, calling Edward Snowden’s whistle-blowing “an act of treason.” But the pinnacle of her career was her damning 6,700-page report from 2014, which she commissioned as the chair of the Senate Intelligence Committee, taking on the CIA’s role in torturing terrorism suspects during the Bush years. In the words of one California political operative, “she was practically melting witnesses with her eyes, just having this steel-trap mind and asking for more details.” It was a moment when even progressive Californians could feel a sense of pride in their unapologetically moderate senator, who may have seen in the CIA’s brutality a breach of the norms she believes in so fervently.

As George Shultz, the former secretary of State, told the New Yorker’s Connie Bruck in 2015, “Dianne is not really bipartisan so much as nonpartisan.” Her devotion is to the system, in which laws are made, regulations are implemented, and oversight is prized. She is stalwart in her conviction that the way to make progress is to maintain open, friendly lines of communication with members of the opposition party, a stance that her defenders argue is crucial to getting anything accomplished in the Senate.

Describing the Ten-in-Ten Fuel Economy legislation passed in 2007 by Feinstein and several colleagues, which ensured that emissions standards grew ten miles per gallon in ten years, Millman said, “Could it have been 20 miles per gallon? Yes, but then the few Republicans wouldn’t have signed on to it, and it wouldn’t have been a law; it would have been a regulation. And when Trump came into power, he could simply have undone it.”

She is probably most famous for her push, as soon as she got into the Senate, for an assault-weapons ban. She had been spoiling for this fight for decades; back when she was mayor of San Francisco, her controversial ban on handguns provoked a recall campaign (she survived it). In 1993, Idaho Republican Larry Craig challenged her by saying, “The gentlelady from California needs to become a little bit more familiar with firearms and their deadly characteristics.” In response, Feinstein said, “I am quite familiar with firearms. I became mayor as a product of assassination. I found my assassinated colleague and put a finger through a bullet hole trying to get a pulse. I was trained in the shooting of a firearm when I had terrorist attacks, with a bomb in my house, when my husband was dying, when I had windows shot out. Senator, I know something about what firearms can do.”

The assault-weapons ban passed in 1994 as part of the crime bill; its 2004 expiration marked the start of our infernal era of near-daily mass shootings. On this issue, Feinstein has been receptive to the activist politics of a younger generation. She appeared in San Francisco with teenage demonstrators in 2018’s March for Our Lives. The footage is kind of heartbreaking from a generational perspective: crowds full of kids who have no idea who the ancient woman on the stage is, what she has lived through, that she has spent decades fighting the battle that has, horrifically, now become theirs.

Feinstein implored her colleagues to act after the murders of 20 schoolchildren in Sandy Hook in 2012: “Show some guts,” she said. She told the New York Times that one reason the Senate could no longer pass an assault-weapons ban was the rising abuse of the filibuster. Of course, Feinstein has been unwilling to commit to ending it.

She acknowledges to me that politics have “hardened” around gun laws in recent decades, saying that “everything has become more partisan than it was when I came to the Senate. When I came to the Senate, Bob Dole was the leader, and he stood up and said … What was it? Tom, help me, what was the quote?” Her aide Tom Mentzer filled in that Dole had agreed that the gun issue was too important to filibuster and put it to a vote.

When I suggest to Feinstein that the partisan hardening has been asymmetrical, that her Republican colleagues have grown more radical and rigid while she and many of her fellow Democratic leaders have been all too willing to compromise, she responded, “Well, yes. I think that’s not inaccurate. I think it’s an accurate statement. What did you first say about Democrats moving?” I repeated that it was the right that has gotten more inflexible while the Democrats have been willing to cede ground.

“I’m not sure,” she responded. “But it’s different; there’s no question about it. And I think there is much more party control. When I came to the Senate, we spoke out, and we learned the hard way, and we took action, and it was clear what was happening with weapons in the country. It still is. And in a way, the weapon issue was a good one because we were able to pass the first bill. When was it, Tom?” Mentzer reminded her that the assault-weapons ban was passed in 1994.

When I asked her about her stated commitment to centrism as a reaction to the tumult of her early political life, she began speaking, unprompted, about Dan White, clearly still appalled by his violent transgressions against the respectability politics that have helped her navigate the world. “A former young, handsome police officer who goes in and kills the mayor,” she said. It was the kind of incident that should grab the government’s notice and compel it to “try to fix those things which are wrong.” But the ultimate lesson she derived from the response to Milk’s murder possesses an almost Olympian complacency: “I think one great thing about a democracy is that there is always flexibility, newcomers always can win and play a role, and it’s a much more open political society, that I see, than I hear of in many other countries.”

From her youth, Feinstein has been an institutionalist, with an institutionalist’s respect for structure, management, and hierarchy as means to manage the rabble of activism and protest. She seems unable to appreciate the possibility that partisan insurgents have overrun those institutions themselves. The crowds who came through the door with battering rams in January 2021 looking to kill a vice-president surely had chilling echoes for Feinstein, but days later, in the name of the Senate, she was defending Ted Cruz and Josh Hawley — a man who had offered up a sign of solidarity to the insurrectionists — in their attempts to delegitimize the election of Joe Biden.

“I think the Senate is a place of freedom,” she told reporters. “And people come here to speak their piece, and they do, and they provide a kind of leadership. In some cases, it’s positive; in some cases, maybe not. A lot of that depends on who’s looking and what party they are.”

“She’s like Charlie Brown and the football,” said Dahlia Lithwick, Slate’s senior legal analyst, describing Feinstein’s unstinting belief that her institution is still functional. “But she doesn’t see that the whole football field is on fire.”

Long before Feinstein sealed the deal with her embrace of Graham, she and her senior colleagues on the Judiciary Committee were criticized for being passive as Mitch McConnell stole a Supreme Court seat from the Democrats. When Republicans crisscrossed the country bragging about holding on to Antonin Scalia’s seat after his death, Democrats did nothing. When Trump appointed the staunch conservative Neil Gorsuch, Lithwick said there was “a little chatter about boycotting the hearings,” but then Democrats “went ahead and had the hearing and confirmed him.”

Feinstein’s belief in the Senate’s sanctity may mean that the enduring moment of her career will not be the assault-weapons ban or her grilling of CIA torturers but that awkward, notorious embrace of Graham. In seeking refuge in government institutions as the shield against instability and insurrection, Feinstein has been unable to discern that it was her peers in government — in their suits, on the dais, in the Senate, on the Judiciary Committee — who were laying siege to democracy, rolling back protections, packing the court with right-wingers, and building a legal infrastructure designed to erase the progress that facilitated the rise of her generation of politicians. But this is who she has always been.

Of that “appalling moment” with Graham, Cleve Jones recalled thinking, “Oh my goodness, you just really cling to this notion of civility and bipartisan discourse. One can marvel at it. But it’s genuine. It’s the core of her.”

The Senate rewards its longest-serving members with power. The most dynamic freshman senator in the world would not have the influence that a senior senator does, which is part of the pernicious trap that has created the bipartisan gerontocracy under which we now wither.

As the senior senator from California on the Appropriations Committee, the temptation to stay forever is great, not just for selfish reasons but for the good of her state. “If we lost her seniority … every other state benefits from California not having seniority, because our appropriations are so much larger,” said Millman.

She has the conviction, held by some in their later years, that she knows better. This is the woman who helped to create Joshua Tree National Park but who also spoke dismissively to the youth activists from the Sunrise Movement who came to her office in 2019, telling them they didn’t understand how laws are made. “I’ve been doing this for 30 years,” she said to the group, insisting, “I know what I’m doing.” But now, with age and all its attendant authority and power, comes serious diminishment.

Multiple reports of her failing memory have been rumbling through Washington, D.C. In 2021, Chuck Schumer removed her from that ranking role on the Judiciary Committee. The Chronicle reported that “the senator is guided by staff members much more than her colleagues are,” a remarkable change for someone who once said, “You can’t let staff run you.” I had let Feinstein’s staff know in advance that I would be asking her about her record on gun reform, and early in our conversation it was clear that Feinstein had come prepared with notes. “The overwhelming statistic is that we have had 200-plus mass shootings so far in 2022, 230 people have been killed, and 840 injured. These are things that we wanted you to hear,” she said, before adding, “So I have this on a card, but I think those are key features.” The acknowledgment of the card felt like a point of pride: She wanted me to know she was sharp enough to know I was sharp enough to know.

That Feinstein may be wrestling with dementia is in fact among the most sympathetic things about her. Getting very old can be hard, lonely; her third husband died of cancer this spring. It is pretty awful now to watch her tell CNN’s Dana Bash, in 2017, that she will stay in office because “it’s what I’m meant to do, as long as the old bean holds up” — and put her finger to her head.

Why didn’t she decline yet another six-year term in 2018 or earlier, when it was perhaps clear that the old bean was not really holding up as she had hoped? Her defenders will lay out all the reasons that retiring in 2017 didn’t make sense, including simply that she won. “Is a diminished Senator Feinstein better than a junior California senator?” asked one of her former staffers. “I would argue, emphatically, yes.” Feinstein’s office released a statement that read in part, “If the question is whether I’m an effective senator for 40 million Californians, the record shows that I am.”

It is also true that she works among plenty of colleagues who are dumb as a box of hammers and have been so since their youth. “I’ve worked in politics my whole life,” said Jones, “and met a lot of politicians who are little more than cardboard cutouts propped up by staff. It’s important to understand that she was never that person.”

But the fact that many of her colleagues, on their best days, are less acute than Feinstein on her worst is exactly the kind of dismal, institutionally warped logic that has left us governed by eldercrats who will not live long enough to have to deal with the consequences of their failures. Feinstein’s defenders argue that there is something gendered about focusing on her overextended tenure, especially when the history of the Senate includes Strom Thurmond, who retired at 100 and was basically not sentient by the end. Chuck Grassley and Patrick Leahy and Mitch McConnell are all in their 80s. Joe Biden first got to the Senate in 1973, and he’s the president of the United States. But being no worse than Strom Thurmond was not the standard to which we were supposed to aspire at this juncture. And while it may indeed be feminist heresy to expect more from women, in fairness, some of those women told us to expect more from them. They were the ones who cast their own elections as the dawn of a new era. They were the ones who argued that every generation does better than the one before.

Indeed, what may be producing the anger at this generation of Democrats is not just ageism, sexism, or the correct apprehension that America’s governing structures incentivize officials to hold on to power sometimes until they literally die. It is also the smug assuredness with which Democratic leaders, in whatever state of infirmity, can still confidently, in the summer of 2022, tell us to trust them and see themselves as a bulwark against the ruin that is so evidently our present and near future.

Perhaps the progress made over several decades in the middle of the 20th century gave Feinstein and her peers an idealized sense of the nation’s institutions as pliable and always improving. She could urge patience and civility because so many structural exclusions had begun to give way. “Women have really grown to the position where their capability is enormous,” she told me. “I see this with great pride: when women come in who are major officers in our military, in uniform, talking about a given problem, and they are articulate, they’re committed, and they make change. And so this is a day that we should not be disappointed in. It’s a day where, if you look back 50 years, it was very different. But progress has been made, and progress will continue to be made. I’m absolutely convinced of that.”

But those articulate women in the uniforms Feinstein fetishizes got there in part because of the social and political upheavals Feinstein has strained so hard to quell. The gains made by women and people of color and gays and lesbians and trans people and immigrants were extracted by force from a system that had been built to exclude them. To be on the side of the system in the wake of victories wrenched from that system was not to be at the center. It wasn’t moderate. It wasn’t neutral.

Feinstein doesn’t subscribe to this reading of American democracy. She believes those at the top of institutions can help those at the bottom get what they want. But American government has become less democratic in the same years that she and her peers have risen to lead it. A majority of Americans want gun control, but the Senate, whose arcane rules Feinstein still submits to, will not allow it. They want abortion rights, but the Court, which was stolen by Feinstein’s Republican friends, is poised to ensure that those rights are erased.

There is a great story in Roberts’s biography about how when Feinstein was on the Board of Supervisors, she got word that the headmistress of her old school, Sacred Heart, had been arrested protesting on behalf of farmworkers with Cesar Chavez. That headmistress, Sister Mary Mardel, told Roberts about how her former pupil had called the jail to speak to her. “Sister, what are you doing in jail?” Feinstein had asked her in alarm. “What about all the white gloves?”