ABUSE OF POWER COMES AS NO SURPRISE.

Jenny Holzer, the 68-year-old Conceptual artist who, in the late 1970s, began papering lower Manhattan with posters bearing “Truisms” she’d written — aphoristic sayings like ABSOLUTE SUBMISSION CAN BE A FORM OF FREEDOM and AMBIVALENCE CAN RUIN YOUR LIFE — has become an idol for our online era. On Twitter, various Holzer bots tweet out her maxims, which read as if they anticipated the medium. (Holzer has nothing to do with the accounts but says she appreciates their humor.) On Instagram, where she appears as a hashtag more than 38,000 times, you can see her words as they appear in the world: on benches, movie marquees, LED panels, light projections.

In real life — which is where Holzer, who does not use social media, prefers to exist — she gave permission last fall for We Are Not Surprised, a #MeToo offshoot, to use her “Truism” ABUSE OF POWER COMES AS NO SURPRISE in an open letter, signed by 9,500 non-male artists, writers, and curators, condemning entrenched sexism in the art world. In January, Lorde appended one of Holzer’s “Inflammatory Essays,” the more aggressive screeds she wrote after the “Truisms,” to the flaming-red dress she wore to the Grammys.

It’s easy to account for Holzer’s contemporary appeal. We’re a culture swimming in indiscriminate words — text messages, news feeds, words on screens, words on billboards — and her old-school maxims slyly lay language bare in all its guises: as cliché, harangue, manipulation, seduction, survival tactic, discomfiting bringer of truth. At a time when hashtags and slogans and memes have never had more power to go viral, her art co-opts the authoritative language of advertising, internet culture, and self-help and asks us to question the power it has to define us.

On a late-September afternoon, Holzer sits across from me at an oak table in her Dumbo studio, narrating projects past and present as they flash by on a TV screen. There is the 1985 Times Square LED sign that made her famous: PROTECT ME FROM WHAT I WANT. There’s Lady Pink, the mural and graffiti artist, wearing an ABUSE OF POWER COMES AS NO SURPRISE shirt. We watch her spectacular 2017 display at Britain’s Blenheim Palace, Winston Churchill’s ancestral home, where, in stark white letters, she beamed firsthand accounts of war. (One reviewer, writing in the Guardian, called it “coldly magnificent and brutal, like being caught inside … the searchlights of helicopters or prisons.”)

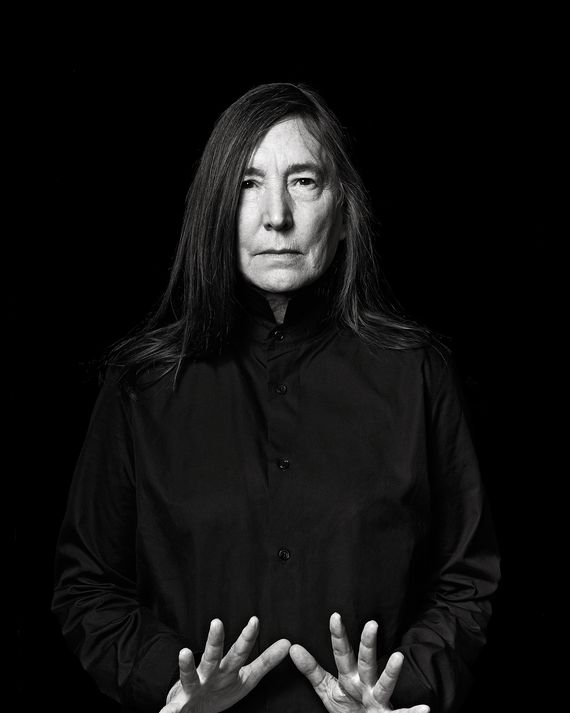

The “Truisms” were anonymous at first. “I have made much of my work sex-blind and anonymous so that it wouldn’t be dismissed as the work of a woman,” Holzer said in a 1992 interview. She tells me something similar now when I ask about her uniform of black jeans, nondescript black sneakers, and a gray men’s button-down. “I’m kind of a cross-dresser,” she says. “I don’t want to be looked at or dismissed, or even attract anybody, as a female. It’s like, ‘Hey, look at the work. What do you think?’ or ‘Talk to me.’ ”

She grew up among horse people in Ohio (her mother taught riding), and there is something solidly midwestern about her: pragmatic, understated, straightforward. “I’m glad to be useful,” she says simply, when I ask about lending her work to the Not Surprised letter. “I have a complex about not being useful.”

Since the early ’90s, Holzer has done mostly LED signs and stone benches as well as light projections on the façades of culturally or architecturally important structures. A street artist at heart, she occasionally engages in anonymous public actions. Last year, in response to the Parkland shooting, she created LED billboards (STUDENTS WERE SHOT; THE PRESIDENT BACKS AWAY) and put them on trucks she sent to cities around the country. She also collaborated with Drake at the Toronto International Film Festival premiere of Monsters and Men, a movie about police brutality. In the atrium of the theater, Holzer projected the names of people killed by police between 2015 and 2018. Names appear and disappear in violent, rapid succession, like lives snuffed out by a gun.

Her writings have always been socially conscious, concerned with power and its manipulations, as well as the satellites that orbit it: money, sex, violence, sexism, love, death. Indeed, hanging all around us are abstract paintings that reproduce redacted declassified government documents from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Political art can often feel limited, the conclusions we’re meant to draw all too obvious. But Holzer leaves the dot-connecting to us. The “Truisms” were written in multiple, often contradictory voices and registers and are both funny and unsettling. “It’s not so much left, right, center as it is about what happens to people in the world,” Holzer says of her work. “People do the same ghastly and good things time and time again.”

ANGER OR HATE CAN BE A USEFUL MOTIVATING FORCE.

Three weeks before Holzer and I meet, she speaks with me by phone from her home in Hoosick Falls, New York. She is about to leave for Spain to prepare for a retrospective that opens at the Museo Guggenheim Bilbao in March, so she has pulled an all-nighter. “My apologies for idiocy,” she says.

She was born in 1950, the oldest of three children (her brother was killed in a motorcycle accident in his early 20s), in the small town of Gallipolis, Ohio. Her father owned a car dealership that his father-in-law (“a small-time Buckeye magnate” who also owned gas stations) had given him. Holzer describes her father as “sort of there and not there” — the result of a head injury. He came home from boarding school one day “and took a running dive off the board, but there was no water in the pool yet,” Holzer recounts. As a child, she found him confusing: “Here was this great big handsome man who was just not quite right.”

She remembers her mother, with whom she was close, as “quite bright” but unfulfilled. “My mother really should have had, oh, four or five jobs, given her energy,” Holzer says. She spent a lot of time deadheading roses and “using Roundup, which is ex post facto terrifying,” she says. “She’d kill every weed in any number of acres, and the second a rose would start to lose a petal, it would have to be lopped off immediately.”

As wry as she is about her mother, Holzer grows serious when talking about her childhood’s darker aspects. When I ask why she signed the We Are Not Surprised letter, she says that as a girl she was repeatedly assaulted. “It started before firm memory,” she says, “and he continued until I was old enough to remember.” She is quiet. “I had that experience, and it’s dreadful, and it’s horrifying that there’s no equality between the sexes — in pay, in respect. It wasn’t hard to sign on for something like that.”

She tells me that around age 4, she began to wear a carpenter’s belt, in which she placed a slingshot, a Swiss Army knife, and other weapons. “I felt good, going around the backyard with that,” she says. “I wanted to have the tools, given what I knew about what people do. Irrational rages, assaults, and so on.”

Still, she believes “good things can be made” of her horrific experience. “I had to do a lot of thinking early on about power relations, and independence of thought, of living.” She resolved to make her own money to control her fate. I ask how old she was when she decided this. “Oh, 5, 6. Again, I saw my very smart, extremely capable mother attacking roses.”

YOU MUST DISAGREE WITH AUTHORITY FIGURES.

When she was a child, Holzer’s only exposure to art was Life magazine; she remembers seeing photos of Georgia O’Keeffe and Pablo Picasso “in his bathing suit.” Although she drew avidly as a young girl, she dropped it in grammar school “to be a regular person,” she says. She remembers a dedicated junior-high art teacher who encouraged her nonetheless, allowing her to make “real art,” like painting and sculpture, “as opposed to embroidered tea towels.” She got a glimpse of what might be.

She attended three colleges in four years: Duke, the University of Chicago, and Ohio University, where she transferred to concentrate on art. During graduate school at the Rhode Island School of Design, she made abstract paintings while experimenting with conceptual projects. She shaped bread crumbs into triangles and octagons, then photographed “pigeons eating geometry.” She sliced up her unsuccessful paintings and turned them into “long, like half-mile-long, ropes,” then photographed them by the ocean — she calls that endeavor “romantic and pointless.”

She painted her studio, every inch, in a blue acrylic wash, her favorite project she’d done to that point, but her teachers, mostly men, didn’t agree. “A group of professors almost threw me out of RISD when I was pretty vulnerable and quite sincere about trying art,” she says. “One said to me something like, ‘You’re the sort of person who would’ve worked on the nuclear bomb.’ Can you imagine?” She recalls “almost falling down the steps” after leaving her critique with him. She became suicidal. “More desperate and speedy than depressed,” she says. “That was my flavor. Self-loathing.”

Salvation came in the form of acceptance at the famed Whitney Independent Study Program. (She graduated from RISD in absentia.) At the Whitney, her “painting was going away,” as she puts it, and she realized the “way forward was to drop the image, which was just abstract color, and go whole hog with the content.”

The “Truisms” were partly inspired by the Whitney’s critical-reading list, which was heavy on philosophy, Marxist texts, and cultural criticism. A series of Burma-Shave billboards from her Ohio girlhood also played a role. “They’d have maxims,” she says. “You’d get them one at a time on interminable car trips with your parents” — e.g., NO LADY LIKES / TO SNUGGLE / OR DINE / ACCOMPANIED BY A PORCUPINE / BURMA-SHAVE. Holzer distilled Enlightenment ideas into the epigrams of advertising and self-improvement: “Derrida and Burma-Shave,” she says.

MOTHERS SHOULDN’T MAKE TOO MANY SACRIFICES.

In 1989, when she was 39, Holzer had two prestigious solo shows, at the Dia Art Foundation and the Guggenheim, and was chosen for the 1990 Venice Biennale, the first woman ever selected to represent the U.S. In the lead-up to the shows, she was also pregnant and gave birth to her daughter, Lili. “This all took place over two years, and Lili had her second birthday in Venice, so it was gruesome. Kind of glorious and gruesome,” Holzer says.

Her selection for the Biennale was not without controversy, especially among more traditional-minded male critics, many of whom thought her writing was banal and her involvement with mass-media technology and techniques not the stuff of art. In The New Republic, Robert Hughes called her work “failed epigrams that would be unpublishable as poetry … their prim didacticism so reminiscent of the virtuous sentiments that the daughters of a pre-electronic America used to embroider on samplers.” But she won the Golden Lion for Best Pavilion for work that included a new series called “Mother and Child” — programmed into 12 LED signs, it was distinctly female and more personal than usual. (When she is criticized now, which is not often, it’s generally for retreading familiar ground; in 2006, New York Times critic Roberta Smith called photographs documenting her public pieces “snoozy.”)

The Biennale text drew in part on Holzer’s experience as a new mother. When I ask about a mistake that still haunts her, she tells me it’s having a baby and doing all three shows at once (her pregnancy was a surprise). “I couldn’t be in the moment and calm for my daughter,” she says, “and I know she suffered. I’m really sorry about that.” She especially regrets working at home while she prepared. “I tried to work in the house so that even though she was with the babysitter, I could walk through. I think maybe that made her feel like I was an insect, something that flies in and out.” Still, she spins the period in her characteristically bleak yet optimistic way: “I wouldn’t care to repeat it, but it’s funny to think that no man has had a C-section, a baby, and done those three shows in two years. Hey.”

YOU ARE RESPONSIBLE FOR CONSTITUTING MEANING.

The day we meet, she has just returned from Spain and is suffering from jet lag. “I’m sleep-deprived, so please plan to write all my answers,” she emails me. “Make them a bit quirky yet deep, moving, indelible.” When I arrive, she takes me on a tour of the “Redaction” paintings hanging around her studio. The obscured lines of text have been painted over in blocks of palladium and gold leaf. The colored rectangles evoke Suprematist paintings, early Frank Stella, and the work of Ad Reinhardt.

She began combing through the National Security Archive online during the Iraq War, trying to understand the decision-making process behind an engagement that confounded her. Now it’s her “midnight reading material,” as she suffers from chronic insomnia. One quite beautiful painting is based on a firsthand account from an Afghan man who was forced at gunpoint to kneel in the snow; layers of palladium cover the man’s handwritten memory of interrogation. In another, all the redacted material is overlaid in gold, save one line: “THEN THE OPTIC BECOMES HOW LEGALLY DEFENSIBLE IS A PARTICULAR ACT THAT PROBABLY VIOLATES THE CONVENTION, BUT SAVES LIVES.”

It’s like a creepy “Truism.” Holzer has created shiny aesthetic objects out of words so awful or secretive they had to be blotted out. Do the paintings draw us in and make us look? Or distance us from the horror? She doesn’t tell us how to think about it. Which means, of course, that we do.

*A version of this article appears in the October 15, 2018, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!