Asia Argento knows about the frozen moment — the one where you shut down and get “tensed up,” to borrow the words of Megan Creydt, one of women who recently accused Charlie Rose of sexual harassment. For Argento, that maddening moment came when Harvey Weinstein allegedly lured her into his hotel room at Cannes back in 1997 and insisted on performing oral sex on her; Argento emphatically said no, but then didn’t fight him off. The incident prompted years of guilt, she told The New Yorker last year, “because, if I were a strong woman, I would have kicked him in the balls and run away. But I didn’t.” Dana Min Goodman and Julia Wolov, who used to perform as a comedy duo, have described a similar sense of feeling “paralyzed” when alleging that at a 2002 comedy festival, Louis C.K. invited them back to his room for a drink, then proceeded to ask if he could take out his penis in front of them before removing all his clothes and masturbating.

But it’s not just brazen or potentially criminal behavior that results in this moment of frozenness. In subtler ways, the moment can also happen in women’s quotidian encounters with men like bosses, boyfriends, and husbands. What exactly is that moment? This is the question Kasia Urbaniak, a dominatrix and Taoist nun turned empowerment coach, has been trying to answer for her entire life. “The problem of female speechlessness — my own, my friends’, my mother’s,” she tells me. “You’re powerful 95 percent of the time but that conversation about your raise is the one that suddenly triggers default behavior — what is that default behavior?” she muses. “Like, what is it that stops you? Because there’s this moment — someone is touching you in a way you don’t like and they even ask you, Do you like that? and you want to say ‘no,’ and yet the word ‘yes’ comes out of your mouth. Or somebody goes, ‘Nice tits, can I come upstairs?’ And it’s just … nothing. That moment. What is that moment?”

In early December of last year, on one of the first formidably cold evenings this winter, a group of 130 women of varied ages and demographics gathered in the lobby of the WeWork space near Bryant Park to seek an answer. Some had come straight from the office; others had come from Utah, Texas, California, or Florida. All were here to attend a workshop conducted by Urbaniak, who has for almost five years been running a secret female empowerment school mostly out of her apartment. The Academy, as Urbaniak and her co-founder and partner Ruben Flores have named it, has so far not been open to the public. (Flores and Urbaniak were together when they founded the Academy; after ending their romantic relationship in 2015, they’ve remained business and creative partners.) In five years, they’ve taught about 500 students. But when I first got in touch with Urbaniak more than a year ago, she was beginning to consider seeking a wider audience. Donald Trump had just been elected and the timing seemed right. Urbaniak teaches what she calls “verbal martial arts,” practical techniques designed to interrupt that telltale moment of frozenness described with bafflement and shame by nearly everyone who experiences sexual assault, including the president’s alleged victims.

Of course, when they founded the school in 2013, Flores and Urbaniak had no idea the issues they’d been exploring would become the stuff of morning TV segments. They decided they wanted to expand their signature courses — Power With Men, an introductory monthlong seminar, and Foundations of Power, a semester-long intensive program (which, at $1,250 and $8,500 respectively price out like the elite private college courses they mimic in class size and format) — without realizing they’d be doing so in the midst of a nationwide predator purge. In this new, welcome, but extremely surprising context, what was intended as a soft open for the Academy has instead become a manic, clamorous, somewhat overwhelming coming-out party.

Arianna Huffington recently invited Urbaniak to her offices (they’re considering assorted collaborations); Urbaniak is fielding book and TV offers; and this evening in Bryant Park, while Urbaniak leads students through role-plays with a real live man impersonating Harvey Weinstein, down to the bathrobe and exact dialogue he allegedly used with his victims, a camera follows her every move. Filmmaker Amy Berg is shooting the workshop as part of a future documentary.

“Who has had unwanted sex?” Urbaniak asks the room. Nearly all the hands shoot up. “Yeah, see, what the fuck?” She says, shaking her head. “Annnndddd …. Who has sucked a cock so you could get out of having sex?” she continues. Most hands in the room dart back up, and a welcome ribbon of laughter ripples through the crowd. We could use a little levity. Urbaniak is a formidable presence, and when she first strode in, wearing thigh-high stiletto boots and a long black skirt with a slit, you could feel the room collectively hush. Though Urbaniak hasn’t worked as a dominatrix full-time in years, she certainly still looks the part, and the philosophy, lingo, and general sense of playful eroticism that pervades everything the Academy does are all straight from the dungeon. Candelabras and dramatic bouquets of lilies are the de facto stage set; students are referred to as “mistresses” and in workshops sometimes dress in corsets and bondage gear; while teaching, Urbaniak wields a riding crop. “You!” blurted out one young woman excitedly when Kasia asks why she’s here. There is a definite cult of personality thing going on between Urbaniak and many of her students, which is part of the appeal of the Academy. But her personal charisma (and the S&M vibe) serves as a gateway, not a crutch.

“I didn’t say no when … ” is where Urbaniak begins her work this evening. The entry point for her teaching is always a deceptively simple question, which she puts to the group; after waiting briefly while everyone writes down responses, she asks for volunteers to share.

“When my husband and I were in a fight and then he wanted to have sex because it turned him on,” says one woman.

“To doing every fucking thing in the house,” says another woman, a few minutes later, cuing a lot of sympathetic nods and another round of laughter.

“When the District Attorney lessened the charges against my abuser because he didn’t think I could handle testifying,” says another woman. The room stills.

Then: “When my daughter was crying this morning and I didn’t want to get her.”

And then: “I didn’t say no to my second set of twins.”

This was maybe half an hour in, a confession uttered with defiant if quivering conviction by a statuesque blonde in her 40s wearing leather leggings and a giant curly lamb fur coat. She offered it to a room full of strangers (she’d come alone) sitting awkwardly close together on folding chairs in an echoey ballroom during cocktail hour, where, it should be noted, zero cocktails were served. And yet this was only the beginning of the evening’s intimate confessions. By the end of the three-hour workshop, one woman announced her relationship with her father had been fundamentally altered; another, a stand-up comedian, declared that she couldn’t wait to “dom the shit” out of her next heckler; many people cried.

Because of high demand, a second Cornering Harvey workshop was already in the works to accommodate the long waiting list. It’s scheduled for February 9.

“I still don’t know how it works,” says Flores. “So much of this journey for me personally is asking the question again and again, like, ‘Why did that exercise work? What happened?’”

And yet Urbaniak’s students attest that it does. “It’s absolutely changed my life,” says Donna Klimkiewicz.

She’s been taking classes with Urbaniak since the beginning, and now assists in many of the school’s workshops. “There’s a certainty in my communication, a sense of authority and fluency. And also a legitimacy when communicating with men of any kind that I didn’t feel before.” What does Klimkiewicz say to friends who are curious and/or worried about all the time she’s spending in what could be easily misread as some kind of woo-woo sex cult? She smiles knowingly. “Usually I just say you have to come.”

The self-help space is a tricky one to inhabit with integrity. This in an industry based — generally speaking — on the reduction of often genuinely meaningful and intellectually hefty religious and or philosophical concepts into bite-sized aphorisms that feel both obvious and vague enough to be metabolized by huge swaths of humanity.

What Urbaniak offers is refreshing because it eschews all the usual tropes of female-focused self-help, from the love-your-pussy vibe of goddess culture (see: Mama Gena) to the bright-eyed, self-flagellating Tracy Flick approach (see: Sheryl Sandberg). At the Academy, you don’t have to strike the right power pose or find your inner Kali or even lie prostrate on a couch and explore how your emotionally withholding father fucked you up with men. Rather, Urbaniak’s approach shares much with Cesar Milan’s, whose book on dog training was a revelation to her when she first started working in the dungeon: “The animal can’t relax until it knows the presence of authority of another, and we are all animals,” she summarizes. Translated to human relationships, this means practicing “the martial art of power dynamics,” a kind of situational cognitive behavioral therapy for the body.

“I don’t give a shit if you love yourself,” Urbaniak explains. “You don’t have to be confident, you don’t have to love yourself, you don’t have to lean in, you don’t even have to believe” — meaning believe in her technique. “You see the results, and you believe them.”

You could say Urbaniak has been preparing for this moment since she was a child. In a journal entry from when she was about 9, she told a fantasy story “about this school that teaches little girls how to hunt out sexual predators and stop them,” Flores tells me, shaking his head in amazement. We were all sitting around a small round table in Urbaniak’s two-bedroom apartment near Carnegie Hall, on a bright spring day last year. Urbaniak is dressed for a Q&A she is hosting later that evening, in a floor-length black gown and her magic boots. Flores, who looks like a young, Hispanic Willem Dafoe, wore a white dress shirt with the sleeves rolled up and dark slacks. Together they convey a decadent old-world formality, like Anne Rice–style vampires, or people who might host absinthe parties. “Yeah, ruthless little girls,” remembers Urbaniak, chuckling. This was around the same time she read Dune and became “obsessed” with the Bene Gesserit, the mysterious matriarchal order who, through extensive mental training (and psychotropic drug-taking) become superhuman and use their powers to help guide humanity. “I was like, I am going to found the modern-day Bene Gesserit!” Urbaniak recalls.

This would have been right after Urbaniak moved back to New York City with her family. Before, she’d been raised in what she characterizes as an “idyllic” Bohemian alternate universe, vagabonding around Europe with her jazz musician parents, Urszula Dudziak and Michal Urbaniak, both of whom are quite well known back home. (Her younger sister, Mika, is also a singer.) “It was this really beautiful community,” Urbaniak continues. “A tribe that moved from one place to another and everyone had a mission, everyone had a job. On the road, every night there was this peak, we had achieved it, and after the peak there was the preparation for the next thing. I thought that’s what life was.” By comparison, American schools seemed like a dystopian prison. “Suddenly I was sitting in a classroom.

Not moving. I had no use. I had no purpose,” Urbaniak remembers. “I realized most people were living this way and I hated it. I detested it. I wanted no part of it. I felt such a strong sense of ‘fuck you.’”

In addition to contending with this drab new reality, Urbaniak was witnessing the disillusion of her parents’ marriage. “The entire functioning of our family organism collapsed,” she says. “As my parents’ marriage deteriorated, I watched my father embody the worst of male power and my mother embody the worst of female powerlessness. It was a fucking nightmare.” Her response was a primal, unspoken, but unequivocal commitment to revolution. “I decided I was going to train to become either a magician or a martial artist,” she remembers. After earning a scholarship to Spence, Kasia dropped out and “lived in a tree in Central Park” for a while. Then she began her training, first as a dominatrix and then later as a nun. “I was like, I’m going to study with every single master in the world, I’m going to rise above this horrible human planet and I’m going to crush men,” she recalls. “I spent years doing that — making money as a dominatrix and studying to be a Taoist nun, learning crazy cool energetic martial art healing techniques. I was going to become superhuman.”

Urbaniak lights an American Spirit before launching into her school’s origin story with practiced flair. “I was one of the highest-paid dominatrix in the world and he’s the Doctors Without Borders guy who negotiated with psychopathic warlords.” She smiles mischievously, exhaling a plume of smoke. Before starting the Academy, Flores worked as a project coordinator for Médecins Sans Frontières, setting up hospitals in conflict zones mostly in central Africa. “After we met, we got involved in pretty much a six-month-long conversation,” Urbaniak continues. “We realized that working in the dungeon and working with the psychopathic warlords had such crazy overlap.”

This was five years ago, after the couple had begun dating and just after Urbaniak had convinced Flores to quit his job to stay in the U.S. and join her revolution. For the prior few months, they’d been having intense conversations about male–female power dynamics, but “there was this friction,” Flores recalls. He was in between MSF missions, but considering returning to Syria. If he was going to stay (with Urbaniak and in the United States) he wanted to balance out their life a bit — “tone down the revolutionary intensity of what we are doing,” as he puts it. He wanted more nights spent holding hands at the movies and fewer holed up inside, high on caffeine, scheming.

“She wrote me this email,” Flores recalls. “In which she said, I know you’ve been asking a little bit more of my time and my attention and you’re entitled to that and it’s legitimate. But … I have to ask you to drop everything and make supporting me and this school the most important thing in your life. I need you to be a total hero on this. Because nothing less than that is going to make it happen, and if we pretend that it will, then we’re going to die a very slow death.” Urbaniak remembers that her hands were shaking when she hit send. But, much to his own great surprise, Flores’s response was an unequivocal yes. “What was clear was that this was exactly what was needed to make the woman that I love happy,” Flores recalls, grinning widely. “There was no faking it. This I could feel. This I could trust. And if I did this, I would succeed in being the man I wanted to be.”

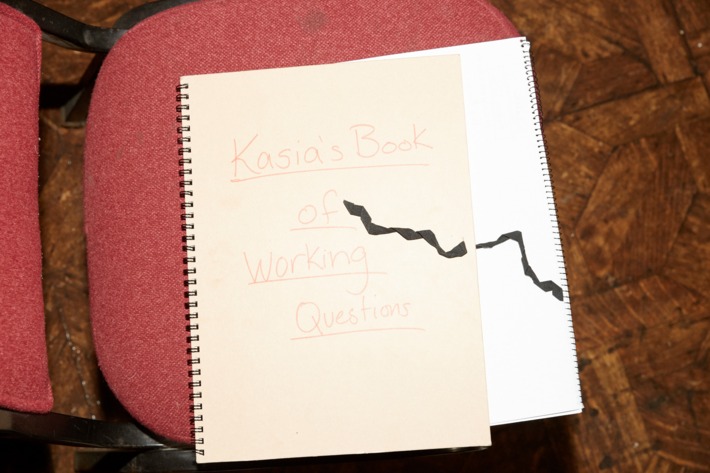

That having been settled, the couple got down to brass tacks. “I was like, okay, so what’s the time line? What are we going to achieve?” Flores remembers, immediately applying his in-country organization skills to this new domestic mission. “She’s like, I have this exercise, it’s revolutionary, I do it all the time and I’ve taught it to friends and it’s changed their lives. I’m like: YES. Tell me all about it! And she goes, it’s called the asking practice. And I go, yes!!!! What’s the asking practice? And she goes, women write down on a piece of paper, I could ask … the name of a man, and an imaginary ask. The goal is not actually to do it, it’s just to list as many things as possible.” Flores makes a stupefied face. “I was like, ummm, we are so fucked,” he remembers. “I said, I mean, we’ve experienced some fairly magical things together and … tell me you didn’t travel the world and come back with … I mean, this is it? Do you see how that sounds absurd?”

It does sound absurd, and yet it can be revelatory. Over the course of the three-day workshop Power With Men, which I attended last year, I witnessed astonishing unburdening catalyzed by a woman merely walking up to the front of the class, Urbaniak’s riding crop in hand, and asking a male-shaped bust to …. take out the trash, or buy her flowers, or fix her apartment complex’s washing machine. “If you make a woman write down 100 asks of men, of different men, like, ‘I could ask Bob to put up the shelves,’ first she’s going to insist that she knows no men,” Urbaniak says. “There are no men in her life.” She rolls her eyes. “I’m like, men in your life includes the doorman. Half the people in your life have penises! The second thing she’s going to say is, If I ask I’ll be in debt. It’ll make me look weak. If I ask I’ll sound bitchy.”

Much of the school’s curriculum is grounded in variations on this asking theme, all meant to shake up the brain, overriding ingrained patterns. In a process Urbaniak calls “sensing and testing,” she uses a stuffed owl to stand in for the wooden owl-shaped dummies her neighbors across the street leave on their balconies to scare off birds. “Just the shape of an owl sending a signal into a bird’s brain — avoid this place — is very efficient,” she says. “So much of the things we’re afraid of, so many of the experiments we don’t conduct, so many of the places we go speechless or hesitate, so many of the places we don’t venture into even though we really want to, are exactly the same as what’s happening to the pigeons. We see the shape of an owl. There’s something that has us go, oh no, there might be danger. So you probe in those places to check if there is indeed an owl there or if it’s just … a toy.”

In a series of assignments students do over many weeks as prep for the Power With Men intensive, they “play” — a favorite Kasia word — with this assortment of different asking practice structures. One setup that I saw generate a mind-boggling amount of emotion via a simple exchange of words is the “rigged no” practice, which goes like this: Think of the most vulnerable request you could possibly make of the person whose attention and acquiescence you most wildly desire, then practice hearing them tell you no. These experiences are like high-altitude training for the psyche; you’re inoculating yourself against future trauma, and discerning which stories you’ve been telling yourself about the threat of those potential traumas are actually true and which are merely stuffed owls.

Once Urbaniak gets her students past that initial most basic asking practice resistance, she tweaks the language. “Usually the way they first phrase it is, treat me more lovingly,” Urbaniak says of the average boyfriend-specific ask. “I’m like, okay, but what is the concrete, specific ask? Pretend he’s a dog! Give him an instruction, like buy me flowers and take me to this movie on this and this date.” What Urbaniak sees, time and time again, is not just an almost comical amount of foot-stomping petulance in response to even doing this exercise, but also, from an Animal Planet perspective, hugely convoluted body language when students finally do. This particular “take me on a date” ask often triggers an artificially high, pleading voice and hunched shoulders, which communicates “both the disappointment she’s going to feel when he gets it wrong and the rage that she feels that she has to ask,” as Urbaniak explains.

Here’s where Urbaniak’s experience as a dominatrix is probably the most apparent in the school’s rhetoric. “We have rage, an outward-moving emotion,” which Urbaniak would characterize as a dominant or “dom” state. “And here we have disappointment, an inward-moving emotion,” which she would characterize as submissive or “sub.” Historically, for the most part, women have been in the sub role, but in the 20th century we’ve both demanded and been forced into more dom roles. This has all happened incredibly quickly, from an evolutionary perspective, and without much expressed cultural awareness or oversight; as a result, we now have an uneasy relationship with both states. “Women are afraid to look like they’re higher than you and they’re afraid to look like they’re lower than you,” Urbaniak says.

She calls the constant, inherently futile attempt to strike that impossible balance “leveling” — as in trying to get on the same level as everyone you talk to, relentlessly micro-calibrating. “My boobs are too small until they’re too big. I’m too quiet and too mousey until I’m too loud. I’m too serious until I’m too funny. I’m too studious until I’m a fucking failure,” she summarizes. In the language of the Academy, the collective state this generates for women is called “compression”: The competing “dom” and “sub” emotions push women from opposite directions, compressing the female psyche until, as Urbaniak puts it, “that tightrope is so narrow that a woman can hardly fucking breathe.”

If you’re wondering why it was often so uncomfortable, even for HRC superfans, to watch Hillary Clinton debate Donald Trump, it’s because she’s “the poster child for compression,” Urbaniak says. “She made sure not to seem like too much of a mom, too much of a kid, too much of a slut, too much of a dom, too much of a sub, too much of a boss. She was not too much a First Lady, not too much a president, she was not too much anything. She completely erased the animal signal of her body. She was impossible to locate. So even if she was telling the truth, it didn’t sound like the truth; nobody could believe her. He was the only one on the stage.”

The solution in such moments, according to the Academy’s teachings, is to change the story. To put the attention out, away from you, and back onto the other person. “Ask him a question! Ask him a question about anything! Ask him a question about asking a question!” Urbaniak encouraged, during the Cornering Harvey workshop, jumping up and down with enthusiasm. “Tell him you like his shoes! I mean, anything.” It’s a tactic Urbaniak learned when training young dominatrixes, who regularly contend with clients pushing the boundaries of the dungeon to see if they could get laid. “We had to make them sexual-harassment-proof,” she recalls. So, if a dude walked in and said, “Hey, this is nice and all, but when are we going to fuck” — a line Urbaniak (and certainly, many a young Hollywood actress) has heard — Urbaniak’s students were taught to respond with playful domination. “Is that what turns you on, making demands?” she might say, striding purposefully toward the slave. Or even, “That’s an interesting tie.” The point is to present yourself as a nonnegotiable force. “What we in the school call the sandbox,” Urbaniak says. “These are the facts, this is who I am, this is what I’m up to. Not threatening the other person but also never giving the impression [you are] in any way negotiable.”

This is exactly what Urbaniak says Cara Delevingne did when, allegedly cornered in a hotel room with Harvey Weinstein a few years ago, she asked him if he’d like to hear her sing. The model’s account, posted on Instagram in October last year, follows a now-familiar pattern: She was meeting with the producer at a hotel, a young female assistant coerced her into going up to his room where she found another young woman, which initially made her feel relieved and safe, but then, “he asked us to kiss.” This is where her story diverges. “I swiftly got up and asked him if he knew that I could sing. And I began to sing … I thought it would make the situation better … more professional … like an audition … I was so nervous.

After singing I said again that I had to leave. He walked me to the door and stood in front of it and tried to kiss me on the lips. I stopped him and managed to get out of the room.”

“She used a tactic we teach in the school,” Urbaniak says when I describe Delevingne’s experience. “She changed the sandbox,” affirms Flores. “I know when I was in those situations,” Urbaniak continues. “I wanted to top the motherfucker, get what I want, not anger the bear and leave with all my parts intact. It was an incredible instinct of hers to dominate the space in the way that she could, to change the conversation, to make it about something else. It was instinct. In her own soft beautiful way she got back on top and he lost his hard on.”

Urbaniak’s initial interest in working in dungeons was inspired, in part, by the iconoclastic, controversial Polish writer Jerzy Kosiński, author of Being There, among other novels. “He was my mother’s lover, who was functionally my stepfather,” Urbaniak recalls. “And BDSM was sort of in the background of his writing.” When she was a teenager, before Kosiński committed suicide in 1991, he was an aesthetic mentor to young Urbaniak, who also takes photographs, paints, sings, and writes. Kosiński’s interest in BDSM initially sparked Urbaniak’s, but the decision to go pro as a dom was primarily a financial one. “I worked as a stripper for like a minute,” she recalls. “And then I was like, I can’t do this shit because it involves hustling for money and I need to be paid by the hour.” She answered an ad in the back of the Village Voice seeking junior doms, and they hired her immediately, though her first session was an utter disaster. “After that, I went to Kim’s Video” — the legendary downtown New York City cinephile haven — “I got a BDSM video and I basically memorized everything she said, and in my next session I said it back verbatim,” Urbaniak recalls, laughing. “It wasn’t something I wanted, it was more like, I’m going to pay for my college and my sister’s college and I’m going to travel the world and become superhuman and this is what’s going to fund me. I needed a lot of money.”

Dom work was a means to an end. And, for a while, part of her desired end was the destruction of her father. “I went on this mission to basically crush my dad,” she says — meaning to confront him with all the ills of his past, the ways in which he’d failed her and the rest of their family. “To bring order back into the world, starting with him,” she continues. “And I did. I fucking crushed him,” she recalls, tearing up. “It was one of the most devastating, disappointing experiences of my life.”

Urbaniak thought she could combat patriarchy by destroying the largest looming representative of it she knew, but once she had her dad on his knees emotionally, she realized she wanted to build him up rather than tear him down. After confronting him with all the sins of the past, “All I wanted to do was to be able to put my head on his lap and have him stroke my hair and tell me a story,” Urbaniak remembers. In that moment, the Academy’s asking practice was born. “I just started asking him for small things,” she says. “Like, Take me to the movies. Or, my dad has the streak of the con artist in him, so anytime I’d have a business deal I’d be like, Dad, what do I do here? And he would just light up. He was so hungry for it. I just kept feeding those requests until I had a dad. Until I had a dad I never thought I’d have. Until I had my dream father.”

For Urbaniak, crucially, men are not the enemy but allies in wait. She began the Cornering Harvey workshop by announcing, “As fucked up as this may sound, I want to start by honoring the patriarchy.” It’s the first step, she says, in “moving past the thing we’re fighting against and to the thing we’re fighting for.” Unlike many women’s groups, men are not only allowed in the school, they’re key to its success. “We include men and the school is co-taught by a man, for which we have received criticism,” Urbaniak allows. “Those accustomed to women’s groups are like, the space has to be pure, you’re making it impossible for women to be themselves if there is a man present, and my answer is always, we’re never going to get this done if it’s just us women.”

Of the 50 or so men the Academy has asked to serve as living stand-ins for all forms of female rage and sorrow, 100 percent have volunteered again, and in some cases, asked if they could quit their jobs and work for the school full-time, or make a TV show about the school, or take classes themselves. “These are regular guys that say, ‘When I see what happens here it changes the way I see the world outside,” says Flores.

“It’s easy to have a bullshitty take on what empowerment is,” says Zac Hill, a partner at Future Labs, an R&D lab for projects that aim to create systemic social value and one of the Academy’s regular volunteers. “Like, no shade to Queen B, but this artificial Sasha Fierce thing where you have to perform power. What Kasia is doing is the exact inverse of that. It’s about being able to have power just as a fact. As a describable, observable phenomenon. And that is the thing that the market isn’t producing good solutions to yet. I don’t know of anyone else who is even training that skill set or is even thinking of power in the context of a skill set in the first place.”

It’s a secondary goal, for the moment, but the Academy is training men, too. “Men’s education [in this area] sucks,” says Flores. “Sensitive yoga dude embrace your inner whatever? Not to criticize other people’s things but … once a guy believes that he’s learned these sensitive ways, it often just creates a very easy veil for them to just continue in the same misogynistic patterns with even more entitlement.” Even men with good intentions often fumble their way into shitty behavior because they have incomplete or bad information. But, “there’s something in understanding power dynamics that’s so compassionate at a time when we need to radically reexamine power in the world,” says Flores. “It eschews all sense of blame, and provides a very gentle access point for us all, so we’re not hacking away at shit,” Flores mimes vigorous humping, laughing. “So we’re not rubbing clits like … ” he moves two fingers back and forth, like a super-aggressive DJ.

Amid a mass groundswell of feminist rage, many guys have felt nervous lately, and it’s easy to imagine that Urbaniak would be first in line to smite the wicked. But revenge is too small a goal for her; it’s beneath her, and, she believes, beneath women. “There has to be more than just shame,” she said onstage at Cornering Harvey, before leading a volunteer through a role play inspired by the alleged harassment perpetrated by Louis C.K. “I respect and honor the punishment phase we are in, but the guy isn’t the enemy, the enemy is silence.” Flores would later concur, likening this whole battle with the patriarchy to his work in actual war zones. “It’s never too early to start talking about what we will do when we put down our guns,” he said. “We fight. But we’re fighting for peace.”

After the workshop, Urbaniak is brimming with excitement that so many of the women who attended already seemed to understand this. As she, Flores, and their team of volunteer mistresses gathered in the empty ballroom, sitting on their heels in a circle like a giddy coven, Urbaniak remarks on how prepared she’d been for a wall of abject rage, and how awed she was to instead find a collective inclination toward empowered softness. “When a woman takes a position of power, she can afford compassion,” Urbaniak notes. The group gets ready to disperse for the evening, plans in place for the next workshop, and she repeats a refrain she’d been echoing all night: “What’s the difference between something that burns up a few news cycles and something that lasts?”