There has been extensive coverage of Trump’s medical report, as you’d expect. Much of it has mentioned the inclusion of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, which Trump “aced,” scoring 30 out of a possible 30, 100 percent correct. The fact that most “normal” people score around 28 is something to be pondered elsewhere. But something about the clock-drawing in particular seems to have caught people’s attention.

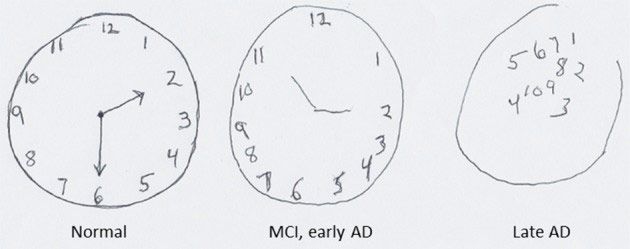

So common are clocks that drawing one may seem like an inherently pointless exercise. It’s something you’d make small children do in kindergarten to keep them quiet on a rainy day. It certainly doesn’t sound like a crucial part of a widespread clinical test used to assess cognitive abilities in a large range of people, including, just recently, the president himself. And yet that’s exactly what it is, a fact that becomes more clear when you see a misshapen clock drawn by someone in even the earlier stages of cognitive impairment. But why is this such a useful test for predicting cognitive decline?

A cognitive assessment is meant to evaluate how good your brain is at doing the things that allow us to function in the everyday world, and the Montreal assessment is clinically useful because it assesses several vital brain processes in a very short amount of time and with minimal tools or oversight required, qualities that are very important in busy clinical settings. One of the core functions, or “cognitive domains,” of a working brain is visuospatial cognition, the ability to perceive objects and understand where they are in space, how they’re associated, the patterns that govern them, and so on. We human beings are intensely visual creatures — it’s our dominant and most important sense, and much of our brains are involved with vision in some form or other. But just being able to see things is not enough; you have to know where they belong or what they should look like, and understand how to achieve this desired state, in order to get things done. And in order to effectively manipulate the things we see in the world around us, something we do all day every day, we need visuospatial cognition.

When you make a bed, arranging all the scattered quilts and pillows into the desired neat pattern, you’re using visuospatial cognition. When you button a shirt, putting the buttons through the correct holes in effective ways, you’re using visuospatial cognition. When you’re playing chess and can work out your next seven moves just by looking at the current arrangement of pieces, you’re using a lot of visuospatial cognition.

It’s not just restricted to one brain region though; it takes a whole network. Seeing the images in your head may be the role of the visual cortex, but you also need to be able to remember what they are and how they work, requiring the memory system governed by the hippocampus and other temporal lobe regions. And you need to be able to process this information, to extrapolate and plan and think ahead, using working memory in the prefrontal cortex.

Visuospatial cognition is widely regarded as an integral part of human intelligence, and one thing that seems to be strongly linked to intelligence and intellectual ability is the efficiency of the connections between the various areas and processes going on in the brain.

The better the connections that exist between your brain regions, the smarter and more capable you’re going to be, just like a fiber-optic cable connection is considered superior to two tin cans linked by a length of string. Therefore, any sign of someone losing their visuospatial cognitive abilities is a sign of underlying problems and a reduced functioning of the brain. But how do you test for this?

Make them draw a clock, that’s how. The very familiarity of clocks to your average person belies their complexity. To draw a clock unaided, you need viable hand-eye coordination, an awareness of spatial arrangements and symmetry, numerical understanding, memory skills, and the test usually requires the subject to draw the clock at a specific time, demonstrating awareness of time and recall.

It might sound simple, and, arguably, it is. But it still requires involvement of multiple neurological processes. If you struggle to draw the numbers in the right order, or it’s all asymmetrical, or you can’t figure out the right time, this suggests that one of those important processes isn’t working as well as it should, which indicates underlying health or neurological problems. So: Trump can draw a clock. Hooray for him. This test still can’t explain why he does not read, or why time has slowed to a crawl since he took office.

Dean Burnett is a neuroscientist and author of Idiot Brain. His next book, Happy Brain, is out in May.